Dostęp do tego artykułu jest płatny.

Zapraszamy do zakupu!

Po dokonaniu zakupu artykuł w postaci pliku PDF prześlemy bezpośrednio pod twój adres e-mail.

ARTYKUŁ ORYGINALNY

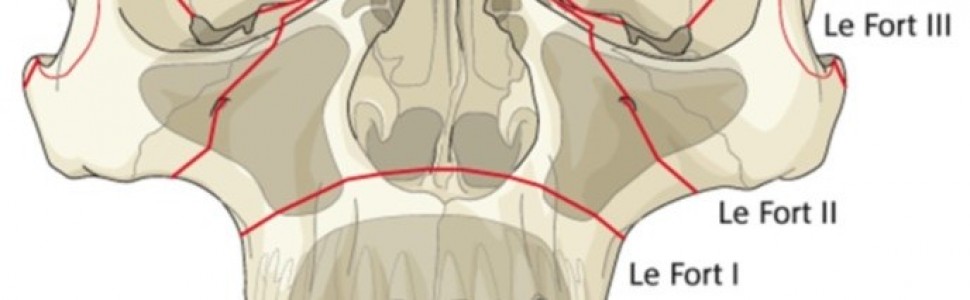

Biologiczne i społeczne uwarunkowania złamań szczęki typu Le Fort I, II, III

Biological and social determinants of type fractures Le Fort I, II, III

Ireneusz Damek, Piotr Arkuszewski

Streszczenie

Wraz z postępem cywilizacyjnym wzrasta liczba urazów środkowego piętra twarzy. Szczęka jako górny masyw twarzy jest w znacznym stopniu narażona na urazy. Etiologia złamań szczęki od wielu lat była obiektem licznych badań prowadzonych w różnych krajach na całym świecie. Za istotne czynniki wpływające na etiologię złamań szczęki uważa się zróżnicowanie kulturowe i ekonomiczne krajów. Najważniejsze przyczyny złamań w obrębie twarzoczaszki to: wypadki drogowe, akty przemocy. Wiele złamań szczęki jest również wynikiem upadków, zwłaszcza ze znacznej wysokości, mniej liczne przyczyny złamań to uprawianie sportu. Większość prac omawiających przypadki złamań szczęki analizuje je na tle różnych złamań twarzowej części czaszki. Dane dotyczące złamań typu Le Fort I, II i III są stosunkowo nieliczne. W klasyfikacji złamań szczęki używa się nadal podziału złamań struktur kostnych masywu szczękowo-sitowego zaproponowanego w 1901 r. przez René Le Forta. Le Fort wyodrębnił trzy typy złamań, które zostały później nazwane od jego nazwiska złamaniami Le Fort I, Le Fort II i Le Fort III. Klasyfikacja ta jest prosta i praktyczna, dlatego wykorzystuje się ją do dziś. Badaną grupę stanowiło 140 pacjentów hospitalizowanych w Klinice Czaszkowo-Szczękowo-Twarzowej Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Łodzi w latach 2000-2014. Dane o etiologii i leczeniu tego typu złamań ujęte są zazwyczaj marginesowo. Ważne byłoby poszerzenie wiedzy o złamaniach typu Le Fort w skali światowej, co stanowiłoby podstawę do dalszych badań dynamiki i leczenia takich urazów.

Abstract

As our civilization advances, midface injuries are becoming more and more frequent. The maxilla is especially prone to trauma, as it constitutes a substantial portion of the midface. For a number of years the etiology of maxillary fractures has been a subject of research in a number of countries worldwide. Cultural and economic differences between countries are believed to be significant contributors to differences in etiology. However, the main causes of fractures are similar across the world. Most studies on maxillary fractures analyze them in the context of different fractures of the facial skeleton. The data on Le Fort I, II and III fractures are relatively scarce. There are no studies on the effective management plan for such fractures, using the least invasive techniques. The classification of maxillary fractures is still based on the division of fractures developed in 1901 by René Le Fort to categorize fractures in the bones of the sinonasal area. Le Fort distinguished three types of fractures, which later came to be named after him as Le Fort I, Le Fort II, Le Fort III. The classification has become widely adopted as it is simple and practical, and has been used ever since. The research sample were 140 patients hospitalized in the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at the Medical University of Łódź between 2000 and 2014. Data on etiology and treatment of such fractures are rather scarce. For that reason it is important to expand knowledge on Le Fort fractures in a number of countries worldwide.

Hasła indeksowe: złamania szczęki typu Le Fort I, II, III, czynniki biologiczne, czynniki społeczne

Key words: type fractures Le Fort I, II, III, biological factors, social factors

Piśmiennictwo

- van den Bergh B, Karagozoglu KH, Heymans MW i wsp. Aetiology and incidence of maxillofacial trauma in Amsterdam. A retrospective analysis of 579 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012; 40(6): e165-e169.

- Al-Bokhamseen M, Salma R, Al-Bodbaij M. Patterns of maxillofacial fractures in Hofuf, Saudi Arabia. A 10 year retrospective case series. Saudi Dent J. 2019; 31(1): 129-136.

- Al Khateeb T, Abdullah FM. Craniomaxillofacial injuries in the United Arab Emirates. A retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65(6): 1094-1101.

- Bakardjiev A, Pechalova P. Maxillofacial fractures in Southern Bulgaria – a retrospective study of 1706 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2007; 35(3): 147-150.

- Chao AH, Hulsen J. Bone-supported arch bars are associated with comparable outcomes to Erich arch bars in the treatment of mandibular fractures with intermaxillary fixation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015: 73(2): 306-313.

- Subhashraj K, Nandakumar N, Ravindran C. Review of maxillofacial injuries in Chennai, India. A study of 2748 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 45(8): 637-639.

- Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fanas SH i wsp. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates – a review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004; 98(2): 166-170.

- Vujcich N, Gebauer D. Current and evolving trends in the management of facial fractures. Aust Dent J. 2018; 63(Suppl 1): S35-S47.

- Bamjee Y, Lownie JF, Cleaton-Jones PE i wsp. Maxillofacial injuries in a group of South Africans under 18 years of age. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 34(4): 298-302.

- Brasileiro BF, Passeri LA. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Brazil. A 5-year prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006; 102(1): 28-34.

- Hallmer F, Anderud J, Sunzel B i wsp. Jaw fractures diagnosed and treated at Malmö Unversity Hospital. A comparison of three decades. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 39(5): 446-451.

- Sasaki R, Ogiuchi H, Kumasaka A i wsp. Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fracture by five departaments in Tokyo. A review of 674 cases. Oral Sci Int. 2009; 6(1): 1-7.

- Salentijn EG, van den Bergh B, Forouzanfar T. A ten-year analysis of midfacial fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013; 41(7): 630-636.

- Gonzales E, Pedemonte Ch, Vargas I i wsp. Facial fractures in a reference center for Level I Traumas. Descriptive study. Rev Esp Cir Oral Maxilofac. 2015; 37(2): 65-70.

- Montowani JC, de Campos LM, Gomes MA i wsp. Etiology and incidence facial fractures in children and adults. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006; 72(2): 235-241.

- Mijiti A, Ling W, Tuerdi M i wsp. Epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures treated at a university hospital, Xinjiang, China. A 5-year retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014; 42(3): 227-233.

- Lee KH. Interpersonal violence and facial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67(9): 1878-1883.

- Andrade NN, Choradia S, Sriram SG. An institutional experience in the management of pediatric mandibular fractures. A study of 74 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015; 43(7): 995-999.

- Allred LJ, Crantford JC, Reynolds MF i wsp. Analysis of pediatric maxillofacial fractures requiring operative treatment. Characteristics, management, and outcomes. J Craniofac Surg. 2015; 26(8): 2368-2374.

- Braun TL, Xue AS, Maricevich RS. Differences in the management of pediatric facial trauma. Semin Plast Surg. 2017; 31(2): 118-122.

- Viviano SL, Hoppe IC, Halsey JN i wsp. Pediatric facial fractures. An assessment of airway management. J Craniofac Surg. 2017; 28(8): 2004-2006.

- Phillips BJ, Turco LM. Le Fort fractures. A collective review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2017; 5(4): 221-230.

- Le Fort R. Ếtude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901; 23: 208-227.

- Le Fort R. Ếtudes experimentales sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901; 23: 336-379.

- Le Fort R. Ếtudes experimentales sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Rev Chir. 1901; 23: 479-507.

- Wanyura H. Urazy szkieletu czaszkowo twarzowego. W: Chirurgia szczękowo- twarzowa. Kryst L (red.). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2007: 247-310.

- Kozakiewicz M, Elgalal M, Loba P i wsp. Clinical application of 3D pre-bent titanium implants for orbital floor fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009; 37(4): 229-234.

- Loxha MP, Sejfija O, Salihu S i wsp. Maxillofacial fractures. Twenty years of study in the department of maxillocial surgery in Kosovo. Mater Sociomed. 2013; 25(3): 187-191.

- Balaji P, Balaji SM. Open reduction and internal fixation. Screw injury – retrospective study. Indian J Dent Res. 2017; 28(3): 304-308.

- Shah S, Uppal SK, Mittal RK i wsp. Diagnostic tools in maxillofacial fractures. Is there really a need of three-dimensional computed tomography? Indian J Plast Surg. 2016; 49(2): 225-233.

- Boole JR, Holtel M, Amoroso P i wsp. 5196 mandible fractures among 4381 active duty army soldiers, 1980 to 1998. Laryngoscope. 2001; 111(10): 1691-1696.

- Lee JH, Cho BK, Park WJ. A 4-year retrospective study of facial fractures on Jeju, Korea J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010; 38(3): 192-196.

- Schön R, Roveda SI, Carter B. Mandibular fractures in Townsville, Australia. Incidence, aetiology and treatment using the 2.0 AO/ASIF miniplate system. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001; 39(2): 145-148.

- Loba P, Sokalska K, Arkuszewski P i wsp. The role of orthoptic assessment in outcome prognosis in patients undergoing reconstruction surgery for orbital blow-out fracture. Klin Oczna. 2014; 116(3): 168-173.

- Kruger E, Tennant M. Fractures of the mandible and maxilla. A 10-year analysis. Australas Med J. 2016; 9(1): 17-24.

- Zachariades N, Papademetriou I, Rallis G. Complications associated with rigid internal fixation of facial bone fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993; 51(3): 275-278.

- Iida S, Kogo M, Sugiura T i wsp. Retrospective analysis of 1502 patients with facial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001; 30(4): 286-290.

- Ansari MH. Maxillofacial fractures in Hamedan province, Iran. A retrospective study (1987-2001). J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004; 32(1): 28-34.

- Królikowska S. Rola stereotypów płci w kształtowaniu postaw kobiet i mężczyzn wobec zdrowia. Nowiny Lekarskie. 2011; 80(5): 387-393.

- Lee KH. Interpersonal violence and facial fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67(9): 1878-1883.

- Bogusiak K, Arkuszewski P. Characteristics and epidemiology of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2010; 21(4): 1018-1023.

- Perkins CS, Layton SA. The etiology of maxillofacial injuries and the seat belt law. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 26(5): 353-363.