*Members of the Upledger CranioSacral Therapy Section of the Polish Society of Holistic Manual Therapy

Peer-reviewed paper

DOWNLOAD PDF

Mailing address:

Łukasz Kaczmarek, PT, CST; Beata Kaczmarek, PT

e-mail: info@holimedica.pl

Abstract

The dynamic development of cranial medicine has resulted in a growing role of CranioSacral Therapy (CST) in dental and orthodontic treatment. The discovery of the CranioSacral System (CSS) has helped practitioners to understand the role of physiological, rhythmical movements of the central nervous system. CST can be incorporated into a dental treatment plan at any stage of treatment. The 10-step Protocol as well as other CranioSacral techniques addressing the bones of the face and mouth are designed to release restrictions within the whole CSS to help facilitate treatment applied by a dentist or an orthodontist. However, the efficacy of this modality in treatment of dental and orthodontic patients requires further clinical studies.

Key words: CranioSacral Therapy, cranium, CranioSacral rhythm, CranioSacral System, temporomandibular joint, bruxism, manual therapy, mouth work

Introduction

Over the past 70 years the progress in cranial medicine has been enormous. In 1948, Dr. William Sutherland published his first paper in which he discussed cranial anatomy and the physiological mobility of cranial bones in relation to each other in response to the so-called primary respiratory mechanism (1). Dr. John Upledger, an American osteopath, contributed greatly to the development of cranial medicine after in 1983 he published a paper entitled “CranioSacral Therapy” (2), in which he presented the basic principles of CST. In 1985, after many years of close collaboration with Michigan State University and having conducted multiple clinical studies of craniosacral rhythm, Dr. Upledger founded The Upledger Institute. A lot of research has been conducted over the last years which validates not only the principles of CST but, most importantly, the existence of craniosacral rhythm (CSR). Especially the work by Moskalenka and Frymann, which describes the physiology of the primary respiratory mechanism, deserve attention, as well as the research conducted by Nelson et al. (4) which explains this phenomenon.

Description of the CranioSacral System and how it affects the bite mechanism

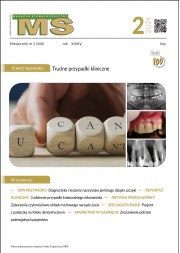

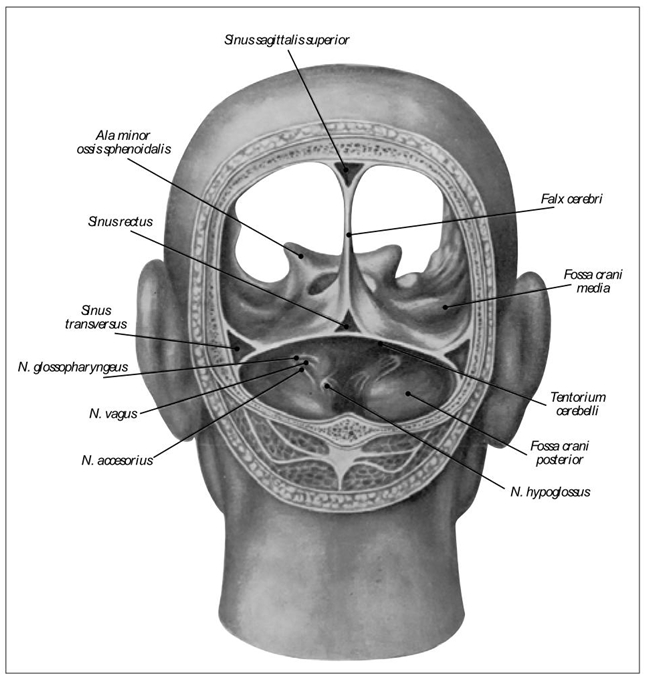

CSS is a physiological semi-closed system located in the dura mater that surrounds the brain and the spinal cord (Fig. 1, 2). Its primary function is the production, circulation, and reabsorption of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It exhibits its own, physiological activity called the craniosacral rhythm. This activity consists in rhythmical expansion and contraction of the whole system to allow the pressure inside to be regulated. This movement can be palpated by a CST practitioner anywhere on a patient’s body and it provides information about any restrictions within the dural membranes and/or the fascia. The intracranial membrane system constitutes an important element of the whole CSS. Any tension or asymmetry within the intracranial membrane system can affect the mobility, symmetry, and amplitude of the movement of cranial bones in relation to each other, which is an important factor in developing dysfunctions that are common in dental practice. These dysfunctions may provoke symptoms like tooth ache, TMJ pain, and other signs and symptoms of the viscerocranium having no apparent organic cause.

Fig. 1. Schematic presentation of CSS, intracranial membrane system – source: Upledger Institute Poland.

Fig. 2. Schematic presentation of CSS, dural tube – source: Upledger Institute Poland

10-step Protocol

A CST practitioner uses, among other things, a 10-step Protocol designed by Dr. J. Upledger, which is one of the basic tools used for evaluation and treatment of the CSS (5). A majority of CSS dysfunctions can be treated with the use of the Protocol. The first stage of the procedure for evaluation and treatment addresses transversely oriented fascia that supports the CSS, including the pelvic, respiratory, and thoracic inlet diaphragms, and the hyoid bone. It is important to complete this stage before cranium is addressed. The next step consists in freeing up restrictions at the occipital-cranial base, sacroiliac joints, L5-S1, as well as in performing dural tube rock and glide techniques. Then, the practitioner uses cranial bones as handles to free up any restrictions within the intracranial membranes. Following the performance of all of the above techniques, TMJ and the bones of the mouth and face are addressed. What seems to be important is that the treatment of TMJ usually takes place after all restrictions within the structures related to the CSS have been removed.

The role of cranial bones mobility in planning orthodontic treatment

Ensuring a free movement of cranial bones at the sutures is an important element of planning orthodontic treatment. Freeing up restrictions within the CSS was already mentioned in the above description of the 10-step Protocol. Many authors argue that cranial sutures are mobile (6-8). Hence, a question arises: to what extent is occlusion related to the mobility of cranial bones? In his work, Barry Libin (9) presents a change in maxillary arch width, measured at the second molars, by 2-3 mm after CST treatment. Ernest Baker described a rhythmical change in the width of the maxillary arch of a patient at a rate of 9 cycles per minute, measured at the second molars (10). Although currently there are only several studies on the relationship between occlusion and cranial bones mobility, the application of CST prior to the commencement of orthodontic treatment, as well as the use of other modalities which involve a gentle mobilization of cranial bones at each stage of orthodontic and orthognathic treatment seems to be well-founded.

Cranial prevention in children

Viola Frymann conducted a research to evaluate dysfunctions within the CSS in 1250 newborns (11). The study has found a correlation between respiratory and circulatory symptoms and the torsion dysfunction of the sphenobasilar synchondrosis and the dysfunctions and restrictions in the mobility of temporal bones. More and more often CST is used in children (Fig. 3) to complement other classical manual therapies which are used to facilitate motor development in the pediatric population, particularly in the case of cranial structural asymmetries or functional asymmetries occurring during a child’s motor development. This approach to treatment allows practitioners to assist the body in its natural self-regulation processes and, as a result, to balance the intracranial membrane system, dural tube, and fascial restrictions within the whole body. Consequently, normal motor development is ensured, as well as a symmetrical development of the cranium.

Fig. 3. Global rotational pattern showing itself during a CST session.

CST process in adult patients

The therapy usually starts with the patient lying in a supine position. The therapist performs a very gentle evaluation of the whole body to assess restrictions within the CSS and tension patterns in the fascia. Specially applied and gentle techniques of compression and traction allow the practitioner to help regulate the tension of the fascia supporting the CSS, as well as to help regulate tension in the intracranial membranes by working directly on the cranial bones. Throughout the session the patient remains fully clothed, which is meant to prevent the sympathetic nervous system from being overly stimulated. In the case of orthodontic treatment addressed to both adults and children, especially important are the techniques for the bones of the mouth and face and the structures related to the hyoid bone. The majority of techniques are performed in the patient’s mouth and are designed to address the zygomata, maxilla, vomer (Fig. 4), hard palate, and suprahyoid muscles.

Fig. 4. Freeing up restrictions at the vomer.

Fig. 4. Freeing up restrictions at the vomer.Because during CST tension is released which often had been retained in the patient’s body for many years, involuntary movements or emotional reactions may occur and they are considered to be a part of the therapeutic process. The patient may change his/her body position on the table, which facilitates the release of tension from the fascial system.

Indications for dental and orthodontic treatment

Amongst many indications, postural asymmetries, hypertonicity, TMJ dysfunctions, bruxism, tongue dysfunctions, viscerocranial pain, and other functional symptoms are the most common ones. CST can also be used to complement orthodontic treatment. An important preventive role in maintaining a balanced muscular, fascial, membrane and bone system of the head and the whole body should also be emphasized.

Discussion

Although CSR has been described and studied many times, and there are more than 100,000 practitioners in more than 100 countries all over the world, CST, being a holistic manual therapy facilitating dental and orthodontic treatment, could and should be applied more frequently. The 10-step Protocol as well as other CranioSacral techniques used in the treatment of viscerocranium help release restrictions within the whole CSS.

Upledger CranioSacral Therapy is a holistic method that supports dental and orthodontic treatment at all stages. Multiple studies of the physiology of CSS validate and justify the use of this method in treatment of many conditions and dysfunctions. A relatively small number of studies of CST as it applies to orthodontic treatment encourages further research in this field.

LITERATURE

- Sutherland W.G.: The cranial bowl. W.G. Sutherland, Mankato, MN, 1939. (Reprinted by the Osteopathic Cranial Association, Meridian, ID, 1948).

- Upledger J.E., Vredevoogt J.: Craniosacral Therapy. Eastland Press, Seattle, WA 1983.

- Moskalenko Y.E. et al.: A modern conceptualization of the functioning of the primary respiratory mechanism. W: King H.H. (ed.): Proceedings of international research conference: Osteopathy in Pediatrics at the Osteopathic Center for Children in San Diego, CA 2002. American Academy of Osteopathy, Indianapolis, IN 2005, 12-31.

- Nelson K.E. et al.: Cranial rhythmic impulse related to the Traube-Hering-Mayer oscillation: comparing laser-Doppler flowmetry and palpation. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 2001, 101, 3, 163-173.

- Gilmore J., Ed. D.: Right Brain, Left Brain Asymmetry Norma. ACLD Newsbriefs, July-August 1982.

- Oleski S.L., Smith G.H., Crow W.T.: Radiographic evidence of cranial bone mobility. J. Craniomandib. Pract., 2002, 20, 1, 34-38.

- Moskalenko Y.E. et al.: Variation in blood volume and oxygen availability in the human brain. Nature, 1964, 202, 4926, 59-161.

- Moskalenko Y.E. et al.: Periodic mobility of cranial bones in humans. Human Physiology, 1999, 25, 1, 51-58.

- Libin B.: Occlusal Changes Related to Cranial Bone Mobility. Int. J. Orthodontics, 1982, 20, 1.

- Baker E.G.: Alteration in the width of the maxillary arch and its relation to sutural movement of cranial bones. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 1971, 70, 6, 559-564.

- Frymann V.M.: Relation of disturbances of craniosacral mechanisms to symptomatology of newborns: study of 1250 infants. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc., 1966, 65, 10, 1059-1075.